The Chinar tree has two distinct native ranges. The larger of the two concentrations is in Greece and the Balkans, and ranges across Turkey. The second distinct native range lies to the east, in Iran. There are isolated populations of Chinars through the Caucasus which connect the two primary concentrations.1

Pliny recorded the westward progress of the tree: by the 1st century A.D. it had been taken to the northern Roman empire, in what is today northern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, along with parts of the Netherlands and Germany.

The date of the introduction of the Chinar tree to the British Isles is usually given as ‘before 1548’.2 Later scholars have cast doubt on this date.3 Isolated specimens thrive under cultivation in the United Kingdom but the tree has failed to naturalize, either in the UK or the US.

The date of these samples in the UK may be irrelevant. The Romans invaded the British Isles in 43 A.D. and occupied the islands and western Europe for four centuries. Where the empire went, the empire builders took their architecture, their mosaicists, and their favorite flora and fauna. By the time they invaded the British Isles, they had already taken the Chinar to Spain and to northern France, 30 miles away across the channel. It is reasonable to expect that the Chinar was introduced to the British Isles during the Roman occupation.

In a move that would prove to be of profound importance to Twentieth-century horticulturists and urban planners, the Chinar had already been introduced to France and Spain by the time the New World was discovered.

While the Chinar was moving west from Greece, it was also moving east from Persia. The tree was first brought to Kashmir from Iran by Syed Qasim Shah Hamdani in 1383. The Mughal emperor Akbar is said to have planted 1200 Chinar trees when he came to power two hundred years later, in 1586. It has flourished there ever since.

The state of Jammu-Kashmir had assumed ownership of all the Chinars, and made the felling of a Chinar a state offense. Yet the trees are still being lost at an alarming rate, and are now considered endangered in the state.

In a remarkable effort to save their Chinars, the J & K Forestry Department is geotagging all 35,000 of the remaining trees; 29,000 have already been tagged. The tag includes a QR code which includes location, health, and other data about the tree.

As usual on a Sunday afternoon we were upstairs reading. I was browsing through an article about the Chinar tree, the iconic tree of Kashmir.4 Gayle was browsing through her horticulture references. It was a typical Sunday.

“What is a Chinar tree?” I asked.

I waited a moment while she checked. “It’s the Platanus orientalis.”

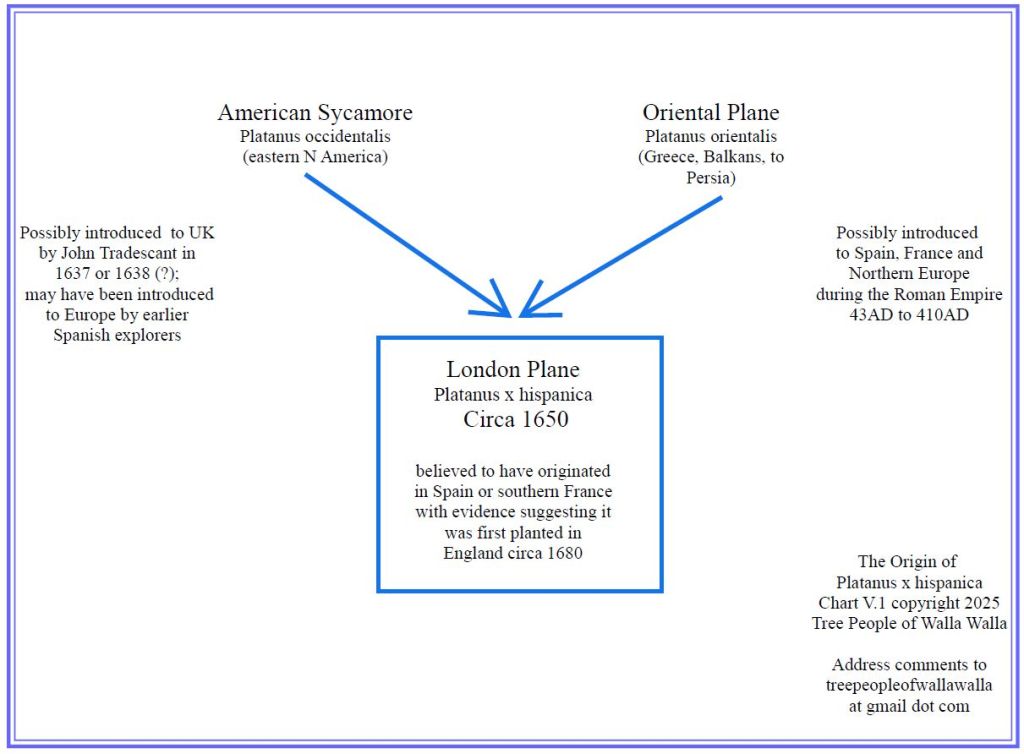

Readers of this web site are familiar with the genus; we have published a number of pages about the world’s largest London Plane tree, a close relative of the Chinar and one of the world’s most common street trees in parks and along public Rights-of-Way.5 Yet we knew very little about the eastern parent of our London Plane until we began reading about the Chinar.

John Tradescant, the head gardener to King Charles I of England, made several plant collecting trips to North America, beginning in 1628. The American Sycamore was taken by Tradescant or other early plant explorers from eastern North America to the British Isles and Europe.

The Eastern Plane and the Western Plane came together and produced a new species: the vigorous, fertile hybrid known as the London Plane. The London Plane has graced the world’s streets and parks since the biological parents were brought together from opposite sides of the globe. Whether this union happened by accident or by design we may never know for certain.

Notes

- For more detailed information see the map by Caudullo, et al, at Wikimedia Commons.

- William Turner, “The Names of Herbes”

- Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles; W J Bean; 1914; reprinted by the International Dendrology Society.

- The article is reprinted in its entirety below.

- The preferred Latin binomial for the London Plane is Platanus x hispanica. It is often known by the synonym Platanus × acerifolia, a later name commonly used in the United Kingdom.

Sources

Our primary source, as usual, is Trees and Shrubs Online. For this article we accessed ‘treesandshrubsonline.org/articles/platanus/ ‘ as well as the pages for Platanus orientalis and Platanus occidentalis.

An essential source for the study of Platanus, especially the London Plane, is Aranya — Plane Trees in London.

Other sources for this article include:

Threat to Kashmir’s iconic chinar trees

BBC, March 1, 2025

Outrage in Kashmir over felling of 500 years old Chinar trees

The New Indian Express, Feb 26, 2025

In the Shade of Chinar

March, 2021

Chinar: The Heritage Tree of Kashmir

Greater Kashmir, Aug 23, 2023

Portrait Of A Tree On Fire

By Rithika Fernandes

Sanctuary Nature Foundation

On the origin of the Oriental plane tree

Danae Danika, et al.

Papers in Palaeontology, Vol 10, #4

Threat to Kashmir’s iconic chinar trees and the fight to save them

Cherylann Mollan

BBC News, Mumbai

March 1, 2025

Was it pruning or felling?

The alleged chopping of centuries-old chinar trees in Indian-administered Kashmir has sparked outrage, with locals and photos suggesting they were cut down, while the government insists it was just routine pruning. The debate has renewed focus on the endangered tree and efforts to preserve it.

The chinar is an iconic symbol of the Kashmir valley’s landscape and a major tourist draw, especially in autumn when the trees’ leaves light up in fiery hues of flaming red to a warm auburn.

The trees are native to Central Asia but were introduced to Kashmir centuries ago by Mughal emperors and princely kings. Over the years, they have come to occupy an important place in Kashmiri culture.

But rapid urbanisation, illegal logging and climate change are threatening their survival, prompting authorities to take steps to conserve them.

The Jammu and Kashmir government has been geotagging chinar trees in an effort to keep track of them and their health. The project involves attaching a QR code to each tree with information about its location, age and other physical characteristics.

“We are ‘digitally protecting’ chinar trees,” says Syed Tariq, a scientist who’s heading the project. He explains that information provided by the QR code can help locals and tourists get to known more about a tree, but it can also help counter problems like illegal or hasty cutting of them.

The project has geotagged about 29,000 chinar trees so far, with another 6,000–7,000 still left to be mapped.

Despite its heritage value, there was no proper count of these trees, says Mr Syed. While government records cite 40,000, he calls the figure debatable but is certain their numbers have declined.

This is a problem because the tree takes at least 50 years to reach maturity. Environmentalists say new plantations are facing challenges like diminishing space. Additionally, chinar trees need a cool climate to survive, but the region has been experiencing warmer summers and snowless winters of late.

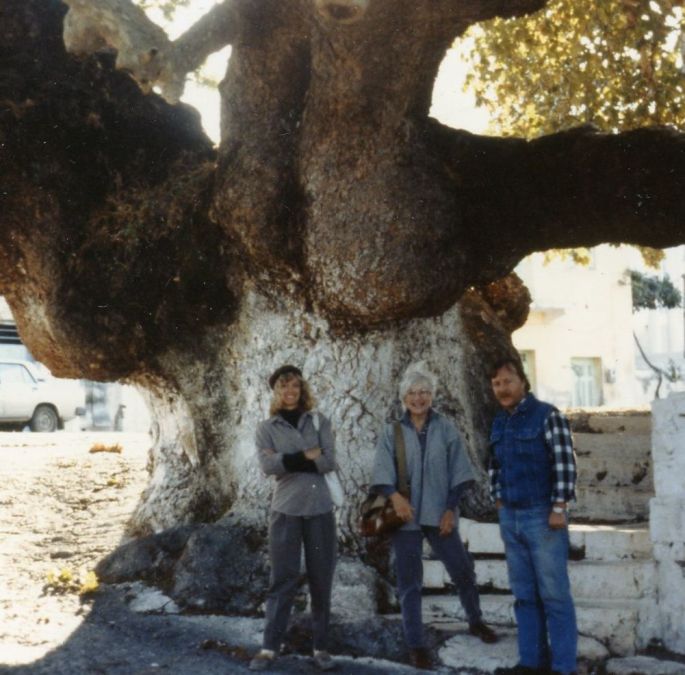

But on the bright side, these trees can live for hundreds of years – the oldest chinar tree in the region is believed to be around 700 years old. A majority of the trees are at least a few centuries old and have massive trunks and sprawling canopies.

The trees received maximum patronage during the Mughal period, which stretched from the early 1500s to the mid-1800s. Many of the trees that exist in the valley were planted during this period, Mr Syed says.

The Mughal kings, who ruled many parts of erstwhile India, made Kashmir their summer getaway due to its cool climate and beautiful scenery. They also erected “pleasure gardens” – landscaped gardens famous for their symmetry and greenery – for their entertainment.

The chinar enjoyed pride of place in these gardens and the trees were usually planted along water channels to enhance the beauty of the place. Many of these gardens exist even today.

According to government literature, in the 16th Century Mughal emperor Akbar planted around 1,100 trees in one such pleasure garden near the famous Dal Lake in Srinagar, but about 400 have perished over the years due to road-widening projects and diseases caused by pests.

Emperor Jahangir, Akbar’s son, is said to have planted four chinar trees on a tiny island in Dal Lake, giving it the name Char Chinar (Four Chinars) – now a major tourist draw. Over time, two trees were lost to age and disease, until the government replaced them with transplanted mature trees in 2022.

Interestingly, the chinar is protected under the Jammu and Kashmir Preservation of Specified Trees Act, 1969, which regulates its felling and export and requires official approval even for pruning. The law remains in force despite the region losing statehood in 2019.

But environmental activist Raja Muzaffar Bhat says authorities often exploit legal loopholes to cut down chinar trees.

“Under the garb of pruning, entire trees are felled,” he says, citing a recent alleged felling in Anantnag district that sparked outrage.

“The government is geotagging trees on one side, but cutting them on the other,” he says. He adds that while authorities remove trees for urban projects, locals also fell them illegally.

Chinar trees have durable hardwood, ideal for carvings, furniture and artefacts. Locals also use them for firewood and making herbal medicine.

Government projects like geotagging are raising awareness, says Mr Bhat. He adds that Kashmiris, deeply attached to the chinar as part of their heritage, now speak out against its felling or damage.

Last week, many posted photos of the allegedly chopped trees in Anantnag on X (formerly Twitter) while opposition leaders demanded that the government launch an investigation and take action against the culprits.

“The government should protect the trees in letter and in spirit,” Mr Bhat says.

“Because without chinar, Kashmir won’t feel like home.”

.